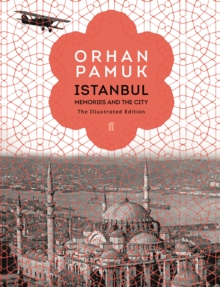

Each one appeared uncaptioned, but attached by theme or atmosphere to the surrounding text. Originally published in 2003, and superbly translated by Maureen Freely, the book explored Pamuk’s childhood and adolescence as a moody loner and aspiring painter who switched medium, from images to words.Īmid his poignant, nuanced and ruefully comic portrait of the artist as a young man in the shadow of faded glories, both domestic and imperial, Pamuk scattered 206 old monochrome photographs. It flows too through the new, lavishly illustrated edition of his memoir Istanbul: Memories and the City. That ambivalence serves Pamuk as sort of creative aquifer that never runs dry.

Torn, like so many Pamuk protagonists, between old and new ways, Cem regrets the loss of traditional charm and grace even as he makes his fortune from galloping modernisation. Where goats roamed, supermarkets, kebab stalls, seven-storey apartments, warehouses and workshops sprawl. The idyllic plateau where he searched for water with the pious, kindly master-digger Mahmut, and fell under the spell of a flame-haired actress in a Maoist troupe, has become a “concrete labyrinth”. When the hero Cem, now a property magnate, returns after a quarter-century to the country town where he worked as a well-digger (itself a wonderful metaphor for Pamuk’s art of emotional and cultural archaeology), he finds that the metropolis has spread to swallow it whole. Newly translated, The Red-Haired Woman spans within its fast-paced, wide-angled 250-odd pages (almost a short story, by his expansive standards) the generational war between fathers and sons, the hidden affinities linking the religious, conservative and secular, liberal sides of Turkish life, the simultaneous appeal of both “Eastern” and “Western” archetypes to people raised on this great civilisational fault-line, and the uncanny way that “The things you hear in old myths and folk-tales always end up happening in real life”.īut, inevitably, the transformation of Istanbul’s fabric and ambience still looms large. So much else happens in Pamuk’s novels beyond the obliteration of decaying Ottoman mansions, misty winding lanes and quaint artisan shops by high-rise towers, urban freeways and shopping malls. These days, he sometimes feels annoyed when critics harp on about the ineffable melancholy and nostalgia ( hüzün is the Turkish word) that haunts his depictions of the picturesque old imperial capital that has mushroomed into a hyper-modern metropolis at such breakneck speed.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)